Superradiant. Block Projects. Richmond. 2012.

Just what is a visual artist supposed to do in a new world of bits and bytes, a world of information overload and pixelated pulsations? Embrace it, of course. That is most certainly the position taken by Janenne Eaton in her riveting, explosive new show at Block Projects; a show that swallows information overload whole and throws it back to the viewer in works that fluctuate from the boldly beautiful to the outrageously garish, from the borderline literal – in You have to make your own fun she playfully embraces the visual language of PAC-MAN, one of the earliest computer games – to the downright apocalyptic – in C23w – falls bright orange enamel paint pours across the canvas like some kind of Biblical torrent of fire via the molten silicon lava of overheated technology. Just what is a visual artist supposed to do in a new world of bits and bytes, a world of information over-load and pixelated pulsations?

Information and communications technology are but one slice of contemporary life that Eaton reinvents. Her ongoing interest in archaeology and both natural and man-made environs remains. Street art rears its head in the almost desperate spray-plea for AIR. Nature itself pops and crackles in Uncanny Val- ley – three seasons where the carbonized silhouettes of ferns and palms are illuminated by electrical explosions. In this visual feast Eaton twists the technologies of archaeology to explore the movements of peoples across time and space, and the residues of social, cultural and material adaptation.

Janenne Eaton’s practice incorporates painting, photography, installation and video. Her works have been exhibited extensively in museums, independent spaces and commercial galleries nationally and internationally since 1978. Eaton’s work is represented in numerous public and private collections including the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, the National Gallery of Victoria, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Holmes a Court Collection and the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra.

Where art and information collide, Ashley Crawford Gallery press release. 2012.

___________________________________________________________________________________

2009 Clemenger Contemporary Art Award. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Janenne Eaton’s background and ongoing interest in archaeology continues to have a profound influence on her work. Each meticulously constructed and crafted canvas reflects the sustained appeal of accumulation – of time and event, of visual evidence, and perhaps most importantly, of human agency. Eaton’s paintings are shimmering meditations on the complex and deeply embedded structures of power and control that have shaped our histories and corral our present. While undeniably and almost defiantly ‘now’, these works bloom from, contain, and somehow seem to also strangely compress, the intersections and differences between the personal and social; the impact of the past, and the overwhelming responsibilities of today (for tomorrow). Yet despite the fact that Eaton’s canvases provide identifiable reference or entry points that enhance connection, their iconography deliberately resists the satisfaction of a neat resolution. On studying these works we are captured in and reflected back from their highly glossy surfaces; suspended within beautiful paintings inspired by ugly things. ‘Where we stand’ determines just what we see within their carefully layered imagery, and there is no doubt that Eaton wants, indeed insists, that we are put to work – made to consider just how our own ghostly presence sits in relation to the various issues – ignorant, confused, powerless, implicated, complicit? – that circulate at their surface.

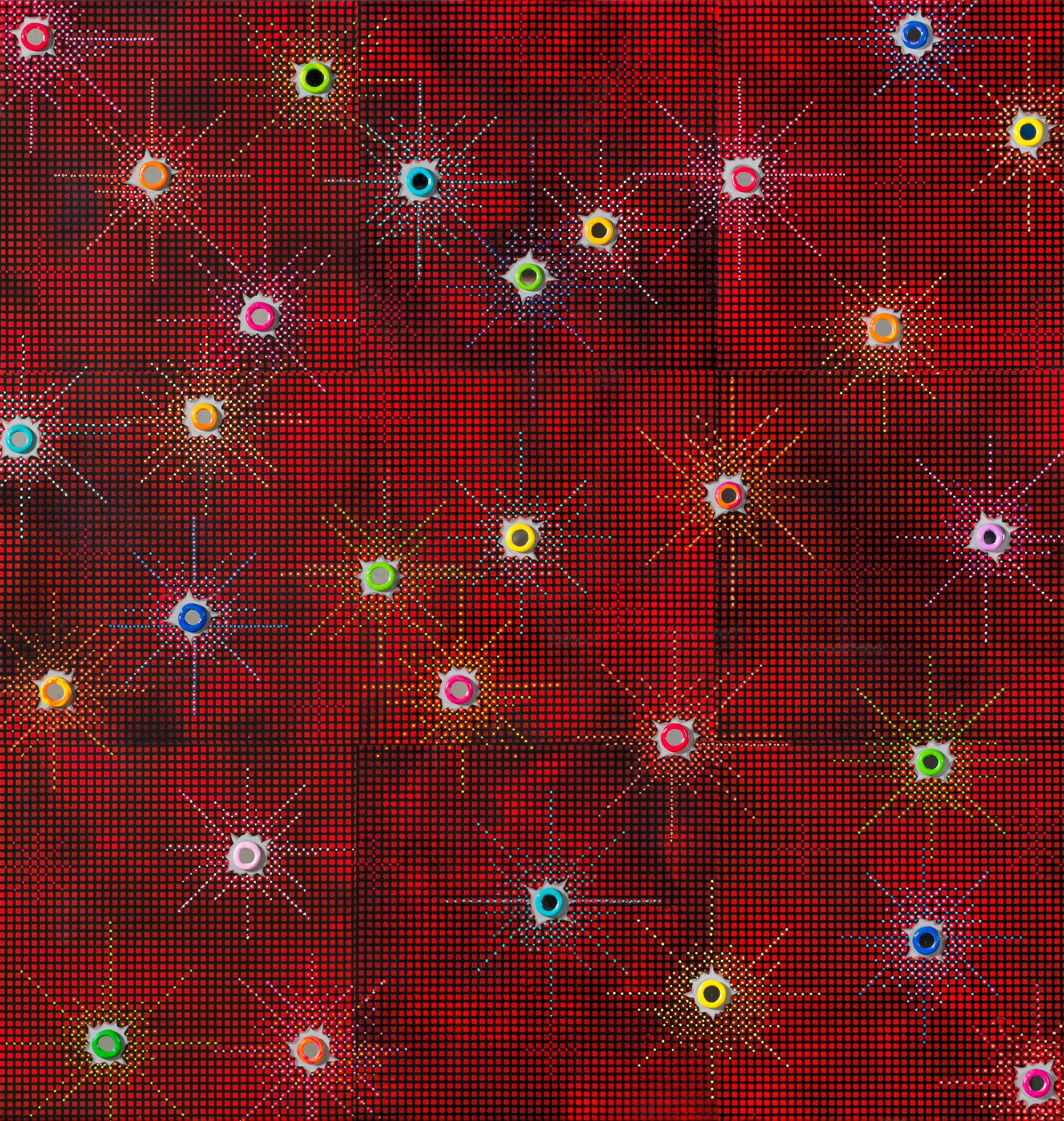

Much of Eaton’s visual influence comes from the flattened space of the screen – from the mediated worlds of film, television and the computer. The bitmap symbols of OUTGO, 2009 for example, are based upon the corrupted code of Eaton’s work; code created when one of the artist’s paintings was fed into the computer and it tried to read it as a text file, rather than that of an image. The fact that the work begins at a point of miscommunication is significant. Eaton consciously attempts to create a kind of digital space in OUTGO; a deeply layered rather than perspectival environment built upon a foundation of dot-screen spray-painted grids. Capturing a sense of a loss of information and the breakdown of communication in its floating, pixelated forms, the painting’s blinking characters also tellingly mimic (in this time of the big GFC [Global Financial Crisis]), the red and green LED feeds of the global stock exchange – abstract information that can nevertheless determine prosperity or poverty, and the power or downfall of nations. Fascinated by the schism between our human (analogue) relationships and an increasingly technological existence, Eaton is interested in the manner in which these changes to communication and our way of being in the world impact upon our empirical reality; how we reconcile our everyday, physical lives with the demands (and potential disappointments) of our new, and supposedly-improved, digital selves.

Kelly Gellatly 'Janenne Eaton'. Catalogue essay for the exhibition 2009 Clemenger Contemporary Art Award. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Recovering Lives. ANU Drill Hall Gallery, Canberra. 2008.

The subject of one series of works in this exhibition is the ‘avenues of honour’, the rows of carefully planted trees on either side of the road that one suddenly and unexpectedly encounters along rural highways in Victoria and New South Wales. Humans have always altered their natural environment to suit their economic needs as well as to express themselves through aesthetic statements. The vocabulary of Eaton’s works speaks of this imposition of the patterns of man upon those of the landscape. Memorial avenues bring together land and history, the two wellsprings from which a nation draws those elements that give it continuity from generation to generation. As Janine Haddow describes it, the natural landscape becomes the cultural landscape, a repository of memory and meaning. It becomes a part of the iconography of nationhood. These are not memorials to great generals or great battles or great armies. Through them the common man becomes visible and for the brief moment it takes us to drive along these avenues the common man occupies centre stage in the historical narrative. Hence they are characterised by an egalitarianism so beloved of Australians. They do not differentiate between military ranks. They are labelled not by order of rank but in alphabetical order. Each soldier from the district in which the memorial drive has been planted is commemorated by a tree and a plaque bearing his name. They are a populist response to the ultimate sacrifice paid by a community’s youth. In time, when, inevitably, the highways are enlarged and relocated these avenues will be marginalised. The power of the symbol will diminish. Less frequently tended, less frequently visited, they will eventually become decommissioned memorials, destined to be lost to history along with the names of those whom they commemorate. The works in this exhibition, like Picasso’s Guernica, ‘allow us to move back and forth between imagination and reason, thought and sensibility, memory and understanding, without imposing one faculty upon another. They demonstrate how visual art can be a catalyst for enhanced intra-societal interaction and exchange, thus expanding the degree of understanding amongst a society’s component elements. They show how the power of art resides in its capacity to play a role in the processes of social change and to be a tool for advancing social justice. And they show how its role in identity formation and in the re-stating of identity through remembering ultimately makes it a vehicle for empowerment.

Nancy Sever.'The Avenue of Honour – anatomy of a monument', Catalogue essay for the exhibition Recovering Lives. Australian National University Drill Hall Gallery, Canberra. 2008.

__________________________________________________________________________

Recovering Lives. ANU Drill Hall Gallery, Canberra. 2008.

The way Janenne began the interview, from the centre at high speed, it was fairly meaningless until I caught the drift: Our speed. Think of how we relate to information, for example the Avenue, how people’s interaction with it has changed from the time it was made to now. People speeding past, maybe they’ll read the sign. It sticks in my mind, the idea I read, somewhere, that the faster we go the more we focus on the horizon. That is like the Avenue, the faster you go, focusing on the road ahead, the less you pick up of what you’re passing through. Our speed is our point of view. How we live with a digital ecology, we’re so often in that space, alert and activated, where time and space is collapsed into a nano-second, a constant flicking present. I like the word longueur – duration – how things form over time, how meaning is only formed through duration, in relation to place, through an accumulation of memories, action, politics, weather. Sedimentation, settling down — that is an action of time. On the other hand suspension, the constant flickering presence, is no time, or rather it is virtual time: an artificial suspension of the material and mental processes.

This was not turning out to be an interview. She was way ahead of me. My preparation had been to jot down my impressions of Janenne’s paintings, accumulated over twenty years. Only one of those notes is worth mentioning, the hypnotic optical effect. Her paintings seem to have their own life. They are alert. Some seem to quiver as if electrified or alarmed.

After Janenne left, I sat down to think through our conversation in relation to the works of art and to retrace the path it had taken (which for me had been unexpected). Traversing the Avenue, the end is the horizon towards which the passing trees are a blur. ‘To quote something I read,’ said Janenne, ‘the faster we go the more we focus on the horizon and the less we experience what we’re passing through.’ From the car moving at fifty kilometres an hour it is not possible to read the names. Few would notice that there are plaques on the trees that form the avenue. Those who read the introductory sign may think fleetingly: this tunnel of trees is a memorial. After the First World War, avenues memorialising the dead ANZACS were planted on the approaches to country towns throughout Australia. In the spirit of the makers of those avenues, Australians to this day vow: ‘At the going down of the sun we shall remember them’. ‘Our speed is our point of view,’ said Janenne. The memorial avenue at Bacchus Marsh in Victoria is not like it was when first planted. The traveller by horse and cart moved slowly enough for the plaques to be seen. More to the point – for seeing – the names inscribed were of people the passers-by had known. Each tree grew for one of the district’s many young people who died in a great war. Recruitment for the First World War was local, soldiers from a district stayed together for the duration, their number dwindling as men were killed. War was experienced as a local affair. Now stately, arching, forming a green tunnel overhead to and from Bacchus Marsh, the avenue, in 1918, comprised mere twigs, inconspicuous in long grass. For as long as the living could not forget, a reminder was not needed. A rough reckoning of time suggests that the community would travel in the shadow of death until the trees grew tall enough to shade the avenue. One thousand local people came together to create the avenue, their work involved many returns to dig the holes, plant the trees, mulch, water, foster and label each tree. They found in the project multiple ways to count over and measure out their dead. The death toll and the length of the avenue was an equation measurable by the number of the saplings to be planted, the intervals between plantings, and the number and names of the dead. Each tree represented a man who did not return from war. The names affixed to the trees were in alphabetical order. With the exception of a nurse (whose inclusion was perhaps an afterthought) the avenue of the dead was in a numerical marching order.

Janenne studied archaeology when she was at university. Photographing each tree in the avenue, and each plaque, she saw how the memorial was shaped by the history of its ageing and maintenance. There were replacement trees and replacement plaques (each with the print-style of its own time), some graffiti, and one private memorial. Attached to the label of one tree was a plastic-covered photograph of a crashed Holden car – a memorial to someone who had died some time before her visit – that was indicative of a new theatre of public remembrance. Along our highways in recent years have appeared crosses and flowers, names and photographs, commemorating people killed at those places in road accidents. The avenues that were planted as civic war memorials nearly a century ago acquire a fresh significance by association with the spontaneous flowering of these roadside memorials.

The Avenue of Honour – anatomy of a monument literally re-traces the avenue. Janenne frottaged each tree. Having made the rubbing of a tree and its nameplate she transferred the image onto a tall banner. On the banner’s other side she hand-copied an image of the tree from a photograph she’d taken of it. Installed for exhibition, the translucent banners were hung in two lines from the ceiling, with each of the two hundred and eighty one ‘trees’ in the place it has in the Avenue. Viewers could weave their way between the trees as well as proceed down the avenue. A few of the banners, only, are included in the 2008 exhibition at the Drill Hall Gallery.

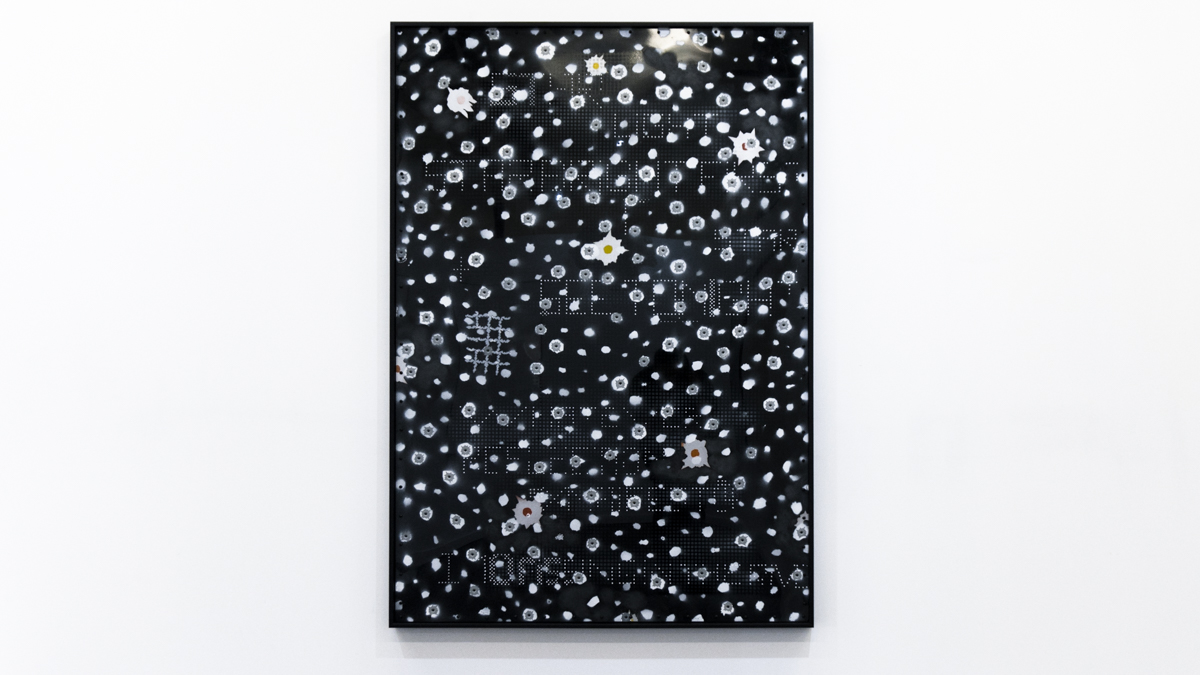

Suspension and suggestion have chased each other in Janenne’s expressive vocabulary like a cat its tail. Typically, the imagery is shadowy, in black, white and grey tones, as in Beep code and Someday, maybe (we’ll meet again). Or it is literal and insistently enamelled (as in Untitled). Colours are either no more than a tinge or they are solid: when a grey painting incorporates lines of solid colour, the effect is strange. In Beep code and Someday, maybe forms and text rise to the surface and dip below, floating in layered grids as if in water. What is enmeshed beneath the surface is only part of the complexity, however. The imagery is doubly inscrutable where parts of the surface blind the eyes with mirror–like reflection. The insistent repetition of dot and grid, together with the ambiguity of the imagery, suggest complexity. The effect is quivering, implying some urgency. However the signs, when readable, are manifestly bland and challenge the process of looking in yet another way by ruling out any need for urgency. Consequently the paintings seem haunted by an unseen or barely-seen presence, yet the promise of revelation comes to nothing.

Recently Janenne introduced an absolute that disturbed the accustomed viewing of her paintings. Viewers like me had settled into seeing in her paintings the expression of life as chronically unfixed and indeterminate. No resting place for the eye or mind was given by the paintings; rather, they seemed to describe a digital world of unreflective immediacy in which, to quote Janenne, ‘time and space are collapsed into a constant, flickering presence.’ Two years ago, in the centre of her exhibition for Helen Maxwell Gallery at Silvershot in Melbourne, was a banner inscribed with the word NOTHING. In the context, Nothing served like a token in a game. It entered the field to cancel the possibilities held out by the exhibition’s imagery of skulls and scrambled computer code. Divested of imagery by the injunction to see nothing, the paintings were stripped to the bare marks of grid and pixel. Nothing continues to be a caveat for Janenne’s recent work, though her exhibition of May this year, ‘Nothing lasts forever’ possibly made the injunction conditional.

When Nothing entered the scene the archaeologist was revealed. David Hansen picked up the cue in his essay for the 2006 exhibition: Eaton also cites her training as an archaeologist as having had a significant effect on her art practice She recalls one particular epiphany, encountering a book of aerial photographs which “revealed a visual, temporal history of crop-growing patterns stretching back to the Bronze Age, moving forward again through Roman times, and so on into the present.” Repetition is everything in Janenne’s pursuit of the grid and dot, yet the appearance of regularity is deceptive. The paintings’ look of computer graphics and the high finish are illusions created by hand with traditional materials and techniques. The dots are hand-painted. The effects are chronically unstable. To create the grid Janenne has, since 2001, sprayed enamel paint from a spray-can through a smallish piece of builder’s mesh: she purloined this one morning from a construction site. Since the mesh obscures the bit of canvas she is spraying, she has to guess the effect she is creating. The piece of mesh is small. Her task is complicated further by having to reposition it several times to spray the canvas. Creating an even effect across the canvas under those conditions is a considerable test of skill. It boils down to experience. The grid is created dot by dot on a basis of intuition born of knowledge acquired over time. The consequences for her art are two-fold. The viewer reads the images as digital and computer-generated, however the paintings reveal the work of the artist: slow, painstaking and repetitive. Janenne’s mark is the regular product of practice and eye judgment, of long time and mental programming, yet its subject is the grid. The subject of these paintings is the grid and pixel. Janenne’s concept is that they are the archaeological imprint of our time.

Mary Eagle. 'Janenne Eaton: Our Speed is our Point of View'. Catalogue essay for the exhibition Recovering Lives. Australian National University Drill Hall Gallery, Canberra. 2008.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Terra Australis: works from the penal colony series. ANU Drill Hall Gallery. 1996.

Quoted in an article by Lynn Magor-Blatch, in the current Print Council Publication. Imprint, the artist says: “By shifting the vision away from the original ‘scenic’ or ‘factual’ descriptions and emphasizing these marginal pictorial elements, I am attempting to suggest a narrative that both calls up the sensations and reveals a sense of the real life experience of the people during the early days of white settlement. Critical to the language of the works is their reference to the imposition of the ‘patterns’ of an alien culture on to that of the indigenous inhabitants and their land. The images explore this violent mapping of terrain, the collision of cultures and the bloody history of well-regulated penal servitude”.

First it must be said that these are quite beautiful paintings. Visually seduced, we are drawn in by their patterns and optical effects. In some works Eaton has used sand and fibre glass mesh and, in one diptych, a panel of embroidered fabric. In each instance these components are fundamental to the ideas and perceptions we are asked to consider.

A prime recurrent pictorial element, the broad arrow insignia that embellished convict uniforms is repeated across a brilliant yellow field, the colour of convict clothing, in Yellow Jacket – afterimage. In At Parramatta, the broad arrow is superimposed on a wave-like field of folds.

Beyond the more general reference to our convict past there is also the underlying idea of convict labour in general and more specifically to women’s work. The arrow is also present in 5040 Maryannes– the name given to female convict servants – but here it is transformed into a subtle pink pattern comparable to a dress fabric.

Terra Australis is a major diptych in which the imposition of order on the land is implied in the left-hand panel consisting of horizontal black and ochre linear patterns and in the right panel by the stamp of the British Museum, familiar from many early botanical and topographical studies, superimposed in a row down an image of densely ordered ferns.

Other references may be found to the ways in which Aboriginal artists depicted landscape and in the right panel you may find an allusion, as I did, to Victorian fabric design yet the inclusion of the broad arrow of the convict suggests another more despairing perception of the land.

Eaton’s abstraction of land-space into horizontal patterns can also take on different contexts as in Australia Felix, the name given to the fertile land south of the Murray River by Thomas Mitchell in 1836, and in the lustrous black reflective surface of Screens and reflections – the Never Never.

While Eaton’s art has become more focused on real historical issues, rather than on the more universal conundrums of human existence that once occupied her, this is an intellectually stimulating group of works that questions our preconceived notions of the past and succeeds in opening up a dialogue on many levels.

We can thank Nancy Sever for curating this stunning exhibition and the art historian Charles Green, who puts Eaton into art historical and philosophical context in his essay for the catalogue, which has been superbly designed by Petr Herel.

Sonia Barron “New visions from an old landscape” Canberra Times. September 1996. Review of the exhibition Terra Australis: works from the penal colony series. Australian National University Drill Hall Gallery, Canberra. 1996.

__________________________________________________________________________

View of Janenne Eaton's current installation at TCB, Melbourne. March 2016

FENCES B/ORDERS WALLS

FENCES B/ORDERS WALLSΩ - notes on the FENCE by Janenne Eaton

My friend Mark Ashkenasy said he liked the bluntness of the title FENCE for my new work. He said the single word was like a ‘blot’. His remark recalled a quote I’d read by writer Cecilia Balli remembering the first time she saw the US-Mexico border fence, the ‘built up’ version of it in South Texas - “When I first drove by it on the way to my uncle’s house, it shocked me. It’s desolate land. To me, it’s very beautiful land. I’m from here. I’m very rooted here, and all of a sudden I see this 18-foot steel fence. It looked like a scar, like a cut that’d just been sutured.”[1] South Texas writer and photographer Gloria Anzaldua describes it as ‘an open wound’. Mark’s comment felt right; as defined, a blot is also a blemish, a stain or a scar.

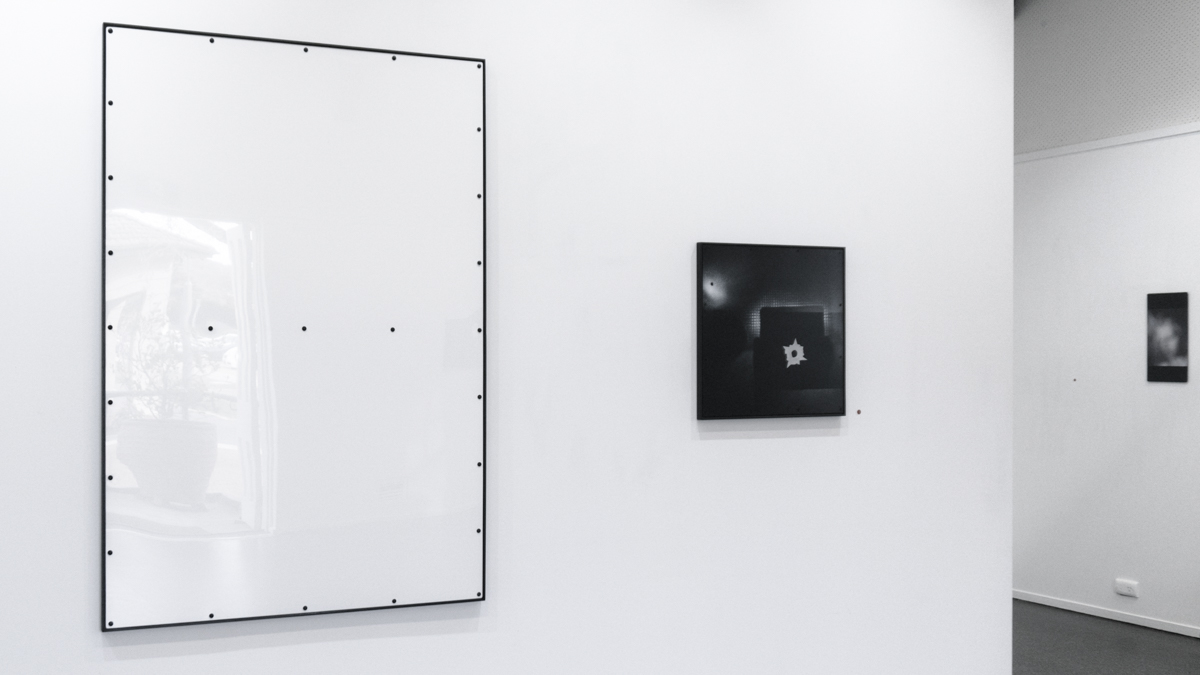

In my previous works, and most recently the installation, Road to the hills – a text for everything and nothing, (2014), I employ highly reflective surfaces to place the audience into the role of participant, reflecting and incorporating the viewer’s body into the narrative space. By Contrast, the illusion of ‘a way through’ is denied by the Fence’s span and the obdurate materiality of its matte surface. What I am attempting here is to conjure a sense of a palpable physicality; a hard-faced sign for the ‘end of the road’. While invoking the definition of fences as barriers, or boundaries to enclose, restrict or hamper, there is a pervasive sense of a phantom presence; almost an aura of something further glimpsed: a blindfold or gag? This impenetrable barrier, akin to a psychological block, suggests the silence of censorship; the muting of political opposition. A silence ‘erected’ for what it might hide as for what it might stop. Like the redacted paragraphs of government files strung across an ideological terrain of lies and obfuscations; recalling the anonymous face with eyes concealed behind the cold black band rather than the pixilated blur.

Invoking the architecture of the universally recognized cyclone wire fence, I wanted the text itself to form the anatomy of the work - the bones of it. The legible spelling, FENCE, flipped into reverse, forms an alternating pattern along its extension. In this way the word, despite its deadpan posture, is written to suggest conflicting and contested realities, metaphorically trapping the audience on both sides of the fence simultaneously: inside and outside its confines. Depending on where you’re standing, (and/or your point of view), determines what we might see within the shadowy shifts behind the mesh. The work’s visual dynamic sets up a rhythmic density that distorts easy legibility, compressing both accessibility and meaning. Are we ignorant, complicit, confused; or simply powerless to change the things that shape our histories and corral our present.

Melbourne\March 2016

[1] http://www.pri.org/programs/the-world